Heart

Igneous lump.

Sayantani Dasgupta Interviewed by Keegan Lawler

By way of introduction to former BOR contributor Sayantani Dagupta’s…

Carrying Instructions

Carrying Instructions by jane putnam perry To dowse is to search, with the aid of simple handheld tools or instruments, for that which is otherwise hidden from view or knowledge. The British Society of Dowsers Dowsing is very literal. The key to asking the right question correctly is to first realize that one question is almost never going to get the answer. The American Society of Dowsers ~ 1. I receive a neuropsychological report as part of legal proceedings after a head-on collision with a car. This is a page from that report. Dowsing Question Putnam genealogy from the author’s family Bible 2. From: Jane P. PERRY <jpperry@*******.***> Sent: Saturday, February 12, 2022 1:44 PMTo: Diane Rapaport <diane@*******.***>Subject: Family History Research Query Dear Diane Rapaport, I hope you are safe and well and have everything you need. I am interested in discussing your services for Family History Research. Specifically, I would like clarity on two family stories. We are purportedly related to the Putnams (who isn’t if your family lived in Salem Village in the 1600’s). My middle name is Putnam, and my Great, Great Grandfather Horatio Perry (b. 1816) married Serena Putnam (b.1818), which explains it, but I would like help learning which branch of the Putnam tree Serena came from, especially because of family story #2. My mother told me we are related to Rebecca Nurse, who was accused of being a witch in 1692 by the Putnam family and who was executed by hanging in Salem, Massachusetts. I have begun research numerous times and have collected all manner of scraps of paper, as well as some family ephemera, but I feel in a vortex. Are my needs of interest to you? Take care and please be safe, Jane Putnam Perry Dowsing Question I feel in a vortex. Are my needs of interest to you? 3. mud sticks weighting my lineage I come from soul sacred soil a mystery of possibilities fractured fissured clay like a heart hardened under horror generations of passed down hurt clotted footsteps of the booted seeking relief from their rage and harms saturate the blessed threshold draw into the cracks rest my language holiness is mindful blood and water and ethers exhumed the short-eared rabbit nibbles tender rain-soaked, sun-lifted leafing what kind of cloud calls out a vertical stack like layers under my feet exhale this d’earthly drought 4. Re: Progress Report External Inbox Diane Rapaport <diane@*******.***> Sunday, Nov. 13, 2022, 7:25AM to me Hi Jane, I have confirmed that Rebecca Nurse was not your direct ancestor, but you are a cousin of her great great grandson, Benjamin Nurse, because one of your Putnam great-great etc. aunts married Rebecca’s great grandson. I’ve also found the deed of Benjamin Nurse’s sale of the Rebecca Nurse farm to your 5th great grandfather Phineas Putnam in 1784. The Nurse homestead became your family homestead. That homestead remained in your own Putnam family for generations thereafter. You are directly connected to the land that Rebecca Nurse and her family called home. As to the 1692 Putnam accusers of Rebecca Nurse, the published Putnam family history that I’ve mentioned, which seems pretty reliable (and I’ll send you copies of relevant pages with my report), has some extended commentary about your 8th great grandfather Nathaniel Putnam. As you undoubtedly know, Nathaniel was a supporter of Rev. Samuel Parris and believed in witchcraft, but Nathaniel signed a petition in support of Rebecca Nurse in June 1692. He did accuse two other women of witchcraft, however, both of whom were executed. Best regards, Diane Diane Rapaport Professional Genealogist Dowsing Question “How must it feel to find yourself face-to-face with someone who has made it clear that he has the power to bring your world to an end, and has every intention of doing so?” ~ Amitav Ghosh in The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis 5. water in water out reckoning the sacred creation yoni from my childhood bring forth my inheritance wrap my memories sand warm and shaping bury us so only our faces show rhythms spray spirit sun breaks into pieces sparkling lens what a nice day dulse source of minerals harvested in the atlantic eat it raw take my children my mother’s ashes in smooth stones a berm separating water from residence but really connecting the two 6. This window was owned by Rebecca (Towne) Nurse’s birth family, photo by the author taken at “The Salem Witch Trials: Reckoning & Reclaiming” exhibit viewed at the New-York Historical Society Museum & Library, on loan from the originally-curated Peabody Essex Museum exhibit of the same title. Dowsing Question “In moments of injustice, what role do we play?” ~ asked by the New-York Historical Society Museum & Library exhibit “The Salem Witch Trials: Reckoning & Reclaiming” 7. strong brown moist loam a history of breaking down and rising the soul spirit of maghemite magnetically removing contaminants sun-lit glittering ripples running like a school of baby mackerel jubilant ribbons of iridescent yellow green a commune of sparkles calling me to the shore to wade amongst the resting matriarchs their manes of bladderwrack breathing with the tide dissolved salts, minerals, and ions not impurities but part of the ancestral sitting with filtered to purity would burn your insides a plop of rain meets ground trickles over stone and soil scrapes against fish and gill carrying this story in ecological DNA 8. Water, a spirit puppet brought forth by the Nonviolent Direct Action Art Team of 1000 Grandmothers for Future Generations. Photo Credit: Peg Hunter, journal.rawearthworks.com Nonfiction Home Art by Holly Willis

Cloudbursts

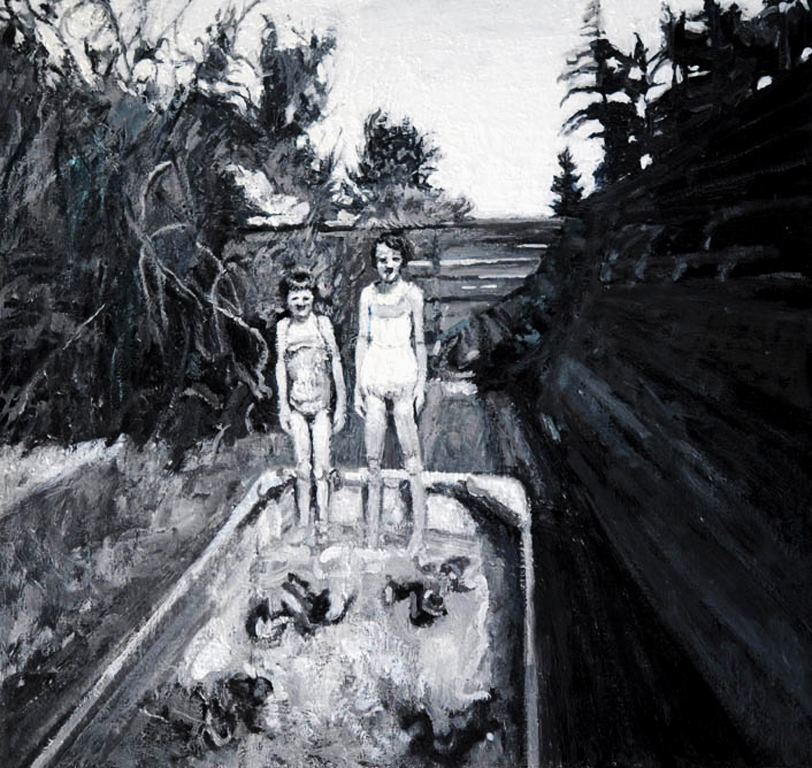

Cloudbursts by Scott Dorsch You are special. Right now, you are in the middle of the living room with your hands out in front of you like a conjurer. Just above your brow is a cloud about the size of a rabbit, raining miniature rain onto a potted lemon tree. A black sheet hangs from the ceiling behind you and scrolls under your feet. It is coarse and sodden with rain. Your feet, too. Holding this pose is painful, but you do it anyway for your father. Your neck and shoulders ache and that familiar sharp bloom of sparks, of a hand gone numb, is back. But you must stay focused. Be still. You are your father’s favorite subject. You were a subject before you could walk. The uncanny prints of a child producing miniature clouds sell like hot cakes at fairs and gas stations all over the Midwest and make your father just enough money to afford the oils and canvas and printing fees. But it is the commercial jobs that earn him a living. Spray guns, ventilators and satin-finish eggshell are Monday through Friday. This latest portrait could change all of that. It could be a showstopper. The sun radiates over your father’s shoulder onto the easel like a spotlight, illuminating ancient dust above, waves of hair that could be your mother’s. It’s a dramatic illumination: the deep, crow-black shadows in the background, contrasted by the bright, angelic subject summoning rain onto lemons in the foreground. The raindrops clinging to the rinds are bright and phosphoric. The cloud, a near-black. The subject, bored. So baroque yet so surreal, critics would say. Perhaps they will comment on the inspiring use of light, the emphatic, no, deft chiaroscuro. But your father’s aim is more specific than that. His vision is more tenebrous, more Caravaggio, more dramatic than just simple deep shading for the sake of depth of field. He thinks this portrait could make him into something more than just a sideshow amongst the beer-can artist at the fairs. He may be hailed as the surrealist Rembrandt of Michigan. Perhaps he could sell more than just postcards and 10x12s, earn an honorary degree from Western or be invited to shows in high-rise New York or the Tate Modern. It could wretch him out of the gaff tape scrum and suffocating fumes of another credit union. Out of this sad cabin, north of town. Perhaps even your mother will come back. Perhaps. It has been ten days and oil has yet to touch more than just swatches and thumbnails. A house is only as strong as its foundation. His eyes dart from subject—you—to the parchment laid in his lap. He crosshatches your cheeks with charcoal in rough, staccato strokes, lifting the portrait to the light every so often to check his work. Satin-finish eggshell forever ornaments his curly black hair (it’s where you get your curls). Satin-finish eggshell hazes his jeans and even his bare feet. Satin-finish eggshell is his scent, his aura. You can’t remember a time when he wasn’t pocked with paint. He works in near silence. Never speaks. Music is distracting. Kids are distracting. You find his new mustache distracting. It seems to be an extension of his wispy nose hairs. Look away. Don’t laugh. Don’t look him in the eye. He hates that. You don’t want to agitate him. He moves like the weather in November. Mercurial, cold. Warm when you don’t expect it. You never know what father you will get. Producing clouds—controlling clouds—requires deep focus. Keep watching the dust dance in the light like krill. Imagine you’re at the bottom of the ocean, the cloud a turtle. Ignore the pain in your shoulders and feet. The feeling has always been ineffable, this making of clouds. You tried to explain it to your mother when you were eight. She was looking out the window when she asked about it. You told her that you could sense the clouds in the room like fish tugging at a line, and you just need to pull them into view. Like this, you said, lifting your hands overhead. A small loaf of a cloud appeared. She smiled. It kind of itches. Stings sometimes. Like static, you said. You’re losing the cloud. Concentrate. There’s a meaty scar on your lower lip from biting it. Tongue the scar tissue and stay grounded. Listen deeply to what’s around you. You can’t lose this rabbit-sized cloud. Your father is so happy with this one. He said it is perfect. Focus on the pencil strokes, the ticks of rain on the lemon leaves. On the texture of the black sheet below you. Your feet. The fan whirring in the other room. The clicks of juncos outside. The brawl of grackles and blue jays. The crying of gulls overhead. The gulls are inland. Storm is coming. Or is it you? Sometimes you can’t tell the difference. The birds make you restless. Behind your ear is a tickle, an itch. You swear it’s a spider. A thick one, like the ones that splay your windowsill at night. Wait for a break in the glances from your father before moving to check. You don’t want to upset him. Minutes pass before your father finally huffs, looks away, and bends to swap his charcoal pencil for a tortillon. He pushes up his glasses and tugs at his mustache. As he rubs his eyes, reach to inspect your nape. “Don’t,” he says without looking. You stop. Shudder. The rabbit-sized cloud expands by an inch, as if it were shocked, hair now standing on end. The rain tightens into a finer mist. Your father raises a brow. Deep breath. Focus. The grackles in the yard. The rain expands. It’s audible once again on the floor, the

when i say my father is homeless, i mean:

when I say my father is homeless, I mean: by Harley Chapman a funhouse version of himself laughing,an eclipse where his mouth should be. so smart. Just like him. he fell off the roof one Christmas& kept on falling. The snow embraced himlike the open sea swallows a sinking ship. dad vs. the State of California. I am talking about criminalities.I am talking about the act of committing a crimeas inseparable from being a criminal. my face is a long stretch of unshavenyears, stacked neatly on the tile. each implosion is entirely my fault(it is not my faultbut it is, still, entirely my fault). a portrait of god in his sunhat, shears poisedbefore an unsuspecting shoot of green. I no longer wish to be called honey,shrink from your touch. my story is changing. I cannot rememberwhat is real & what is just a name. fuck the government. Fuck the law,the police, the purse-clutchers,& every asshole with a brand-new car. an alternative phrasefor airing your dirty laundry isI have nowhere left to hide. I made a mess of it, drank myself stupid& rode that white line like a bronc. the record is stuck. A scratchy repeat:just like him. each year feels more & more like a dare. shame is a debt unpayable. Please,don’t make me explain. Poetry Home Art by Belle Dorcas

Girlhood Sonnet

Girlhood Sonnet by Sophia Ivey I lost my girlhood when my brother ripped out my first baby tooth. I can still rummage through my mother’s attic to find the VHS tape of him holding the small bleeding thing with his hands as if it were a rock bass he had just caught down at Lake Apopka. I told my palm reader this and she insisted I find all of my baby teeth and burn them to ash. I don’t. I keep them in my nightstand, though, most nights I am eager to flick my lighter in the little girl’s direction, burn each tooth to ash, bury each crumb into the dirt so I will not be reminded of things that used to be mine to hold. It would be easier, I know, but instead, I am determined to suck on each tooth like a cherry sour until it is sweet enough for me to spit out. One day, when I am done, I will rest them on my kitchen windowsill. Dry them by the wishbones I save. Like a stuffed rock bass hung on a living room wall I will find pride in preserving a slaughtered thing. Poetry Home Art by k kuulz

Gub Dog

Gub Dog by Addy Gravatte Dedicated to the Holy Body of Saint Margery Kempe I want my real red blood on that faux pink fur But then it’d be burgundy— I’m too putrid for today Nobody don’t avoid me! Before you are very stupid and then you are smart I have always been a witch And I have always been obliged To tell them I am no When I was young I’d get a creature in my stomach And close my eyes I’d know I’d see My flesh, contracting to its slimmest space, Then expanding to its largest possibly —rapidly contracting, ‘twas gut-stuck between the two Until I remembered my tangible body It was proto-sexual for me! I am gross, oh I am a gross thing. Poetry Home Art by James Kelly Quigley

On the Other Side of the Wall

On the Other Side of the Wall by Andrea Bianchi When I hear the girl’s scream pierce the cracked plaster between the new guy’s apartment and mine, I do nothing. My eyes widen, waiting toward the wall in the 1:00 a.m. dark. My back tenses against the mattress. My legs stiffen beneath the covers in the center of the bed. My breath halts. the way it froze in the grip of Rod’s icy fingers on that night two winters ago when his elbows pinned my breasts to our bed and his hands compressed the tissue of my throat, his thumbs collapsing my airway. Flattening my larynx. So when I opened my mouth to try to scream, it did not make a sound Silence now. And then a thud. Perhaps a faint scream. Perhaps I am imagining. I unclench my fingers and pull apart the heavy covers. Test my feet on the floor. My knees wobble. I tiptoe barefoot to the bedroom wall and press my ear against its smooth cool. Maybe thudding with the bass of the new guy’s stereo. But just the ticking of a pipe swishes within. I tip-toe across my apartment, to the opposite wall, maybe echoing with the shrieking laughter of the old woman’s favorite late-night talk show. But against my palm, the plaster flattens, as lifeless as a blank TV screen. Then a thump. A far-off wail. Maybe out on the city streets below. I tip-toe to the balcony and peer down to the sidewalk, where teenage girls used to squeal beside the boys they liked as they pedaled toward the last suburban train. Back before the sidewalks emptied, eerie, silent, save for the wailing sirens of police cars, flashing their blue rays into vacant storefronts as if with some kind of ultraviolent cleansing agent, some cure for the strange new virus that has come to hover above the whole earth, to choke the air, strangling the lungs of the rare masked pedestrians who dare to sneak down the downtown sidewalks beneath my balcony. But tonight, far below, no one is wandering. The only wailing is the wind. I clutch the railing. Inhale to slow the palpitations in my throat—a heart condition that the doctors in disheveled white coats on TV have warned might turn deadly, even in young people like me, if I were to breathe a contaminated stream of air down there, beyond the safety—and the isolation—of my apartment walls. A crash against the plaster. A rattle of the dishes on my kitchen shelves. I march across the floorboards to the wall that separates me from the new guy’s fist. But as I raise mine in response, to pound my reprimand, shout my threat to summon the police, I hear Rod’s long-ago curse, spat out after my hands grasped at our old apartment’s doorframe, after my feeble cry for help bounced and slid down the outside hallway’s walls. “Now you’ve done it,” he declared as he slammed the door against my fingertips. “Now the police are going to come, and now I’m going to get my gun.” I know that if the blue beams of police flashlights were to sweep up tonight from the streets and pierce through the new guy’s door, he too might flash a revolver in response to the police pistols, and then bullets might rip apart the plaster. My hand drops. My palm opens, empty. The silence stretches out the length of the wall. As the blue-lit numbers of the clock on the stove flash past one by one, cleansing the last echoes of the girl’s screams from the quiet darkness of my apartment, I imagine a corresponding blue glow in the room next door. Perhaps a football game replaying on the TV screen. Or maybe a more scripted sort of gore, flashing through some slasher plotline, perhaps prompting the girl’s frightened screams. Perhaps that crash was simply the slamming of a cabinet as the new guy retrieved snacks to accompany the horror film. Perhaps any actual horror was only my imagining. ***** I started imagining the details of the new guy’s life the night he emerged, mysterious behind his mask, from our building’s elevator. As the doors slid open, his frame blocked the entrance with the bruising bulk of a football player, perhaps an offensive tackle a few years ago on his college team, his torso wider than the pizza box in his big-knuckled grip, ready for the game later. The bill of his back-turned cap, which bore Rod’s favorite team logo, tried to suppress the tufts of brown hair punching out in all directions from his head. The edge framed his blue eyes, steady above the blue edge of his mask, as his eyes pierced the hem of my miniskirt and scraped down my bare legs to my heels. I stepped toward the elevator to slide down to the mailboxes—to the packages of stilettos and party dresses I had begun ordering in my isolation, in anticipation of far-off, imaginary parties—when the girl materialized. In the shadows behind him, she wore no mask. Only a kind of grimace, her lower lip twisting. Her eyebrows arched, as if trying to form a protective canopy above her body. She shuffled off toward his new apartment behind the stubborn wall of his back. Then the elevator doors closed into a barrier again between me and them. Through the wall later, though, I heard him yell. “Football, baby!” he said. “Let’s pound some skin!” His bare feet no doubt thumping one after the other up onto the coffee table, his hand stretching out with a beer bolted to one knee. On the other knee, perhaps the girl’s palm was

Take Care.

Nonfiction Home Art by Judith Skillman Take Care. by Nicole Morris The biopsy revealed the start of tooth and bone material, keratin and hair, the beginning and ending of what would have been my twin at conception. Located on the right side of my uterus, holding this flotsam and weighing just under a gram, the equivalent of a single raisin or a quarter of a teaspoon of sugar, was a tumor the size of a plump grape. We won’t have oncology’s final report for ten days, but it’s looking good. I don’t see any cause for concern. The surrounding tissue was clear, and it looks good. You did great. In my head I thought, how does a person unconscious, under the backward counting water of general anesthesia, do great? Did I take the medicine well? Or did she mean my body did great under the pressure of foreign instruments being inside of it? Did I do great with the stress of my skin opening under bright lights with masked faces? The origin story of my womanhood and the site of my motherhood the main character in the operating theater. Did my wounded womb do great in not fruiting cancer? The surgeon told me this very good news while looking past my shoulder at the chrome wall clock hung above a pastoral scene of baby animals circled together under a sunless blue. Breathe, the poster commanded. She avoided eye contact as she spoke to me, which struck me as odd, evasive even. But this is good news, doc. I wanted to say “Doc” the way Bugs Bunny did. Maybe she was lost in her own thoughts while she autopiloted this update. Was it too late in the day for a coffee? Would that ruin her sleep? Did she leave the chicken breast out to thaw? Would her son call that evening? Would he remember today was her birthday? Or maybe she was embarrassed to see me, the obediently sleeping patient, now awake, eyes open and unblinking. This peculiar girl, me, needing one ovary removed, along with a cyst, and while we’re at it, let’s tie up those tubes, too. Weeks before the procedure, this same doctor tenderly, softly, delicately, asked if I’d want to be sterilized while they were ‘in there.’ It would be painless, and my insurance covered it. Sure, I said. Fuck it, yeah, why not. I thought I saw her flinch internally at how easily I agreed to close down shop, to seal off the dam. I’d had two babies, now high schoolers; I saw no need to be greedy and ask the stork for more. Plus, I flashed on how liberating it would be to have unsafe sex with no fear of pregnancy. Sexually transmitted illnesses were always the lone bullet in the game of one-night stands and casual encounters; they were resolvable. Mostly. But an unplanned pregnancy in a country where politicians were pushing for murder charges to apply to abortion, that escalated the self-harm of Russian roulette to a wider and more permanent wound. Did she remember that conversation now? Or was she offended when I showed up for surgery this Tuesday, at five in the morning, in the newly remodeled outpatient wing of the Catholic hospital on the far east side of town, with a fresh Brazilian wax? In preparation for this procedure, even though no one would be going near my down there, I paid eighty-five dollars to have it all removed. It felt like a good-mannerly thing to do at the time. And an expensive gesture of anxiety at being naked in a room full of strangers. A Brazilian in the middle of a snowed-in winter up in the mountains of New Mexico during a dating slump when not a soul was visiting my down there was a cost I felt I needed to pay. A tax. A toll paid without being asked so that, while the surgeon would be bypassing that now hairless seam between my legs and going straight to the middle of me by way of lower abdomen into the uterus, landing on fallopian tubage, she would see that I went to painful and costly lengths to take care of my womanhood. What’s up, Doc? I said it without meaning to. I was thinking it, but now I’ve said it, interrupting her post-op care instructions. No water on the wound site for six days; no excessive activity; expect some spotting; no sexual intercourse for four weeks. Uh. I—she looked at me now. Shit, sorry, I offered. More embarrassed at my Bugs Bunny outburst than at the bit of drool that came with it. Why was my face numb? I can’t feel my face when I’m with you. Who sang that? The Weeknd. I need to remember to listen to that song on the drive home. Wait, when am I going home? Like she could hear my doped-up thoughts inside my head, she returned to my hearing ears now with, It’s fine. The anesthesia can have a euphoric effect. Makes some patients find themselves saying or doing things they normally wouldn’t. Yes. What? Oh. Sorry. I thought I heard a question in there. It took all of my facial muscles to not laugh. More drool. I lifted up my paw to wipe my face elegantly. With my paw. Wait that’s my hand. Why is it furry? Doc, I feel weird. Then I laid down on the paper-sheeted table I’d been sitting on. No memory of arriving in this room now. What time was it? I’ll close my eyes for a moment and get my shit together. That’s normal, you’re ok. The anesthesia will fade from your system in an hour or so. I have a note here that your ride is waiting for you. Can you hear me, Nicole? Ok good. I see you nodding yes. Your ride is here, er, Amir? Amir. He is ready for you,

I Was Waiting for My Turn and It Almost Killed Me

Nonfiction Home Art by Patrice Sullivan I Was Waiting for My Turn and It Almost Killed Me by Maureen Pendras Were someone to ask me now, after it all, the feeling of a dying organ, I’d still struggle for words. It might be better represented in sound. Something discordant, soft then growing louder but unnerving. You’d want to get up and move around; walk it off. Even better—a drawing. One panel: a swimmer moves about on the surface while underneath a large, dark shape lurks. Nothing yet has happened—but it will. The large shape kicks closer then recedes, in and out of focus. Impending doom. I would not be the swimmer, or the shape, or the water itself—but the totality of the thing, all of it together—about to become terrible. I was doing what they asked of me. Waiting. I didn’t think I should be waiting but what did I know? I was the one in the gown, with the pain, not the one holding the clipboard, making decisions. Initially, I’d had short, sharp pains in my abdomen—distinct and obvious. I tried to reshuffle the order of my body as I sat in my chair at work: lift up my ribs rather than rest them on my stomach; shift backwards and stretch out the line of my body; pull my head up like it was tied on a string—none of these movements helped. This feeling, like a cord stretched to its limit, would not go away. I called my doctor’s office to get an appointment that day. “It’s probably your appendix,” said the one available doctor, noting pain more on my right side. “Let’s get you downstairs for an ultrasound. They’ll get you in-and-out, then you can come back here, and we’ll go over it.” He nodded reassuringly and I felt some relief with the possible diagnosis. When I came back though, thirty minutes later, his mood had shifted. He stood at his workstation and there was no avuncular looking it over together. We stood right there in the hallway as he explained: “Call a surgeon,” he said flatly, shaking his head. “You’ve got an eleven-centimeter mass in your abdomen.” “A surgeon?” I asked. I imagined quiet conversation and time consider options. Mostly I imagined time to think. When I asked him if I’d be able to work the next day, he looked dumbfounded and repeated, “You need a surgeon.” I was thinking about the wrong thing. Even in this swirl, I noticed a question looming there, just say it, just ask him, “But it’s not cancer?” Was I even supposed to say the words? Admit its potential in my mind? I was in superstitious territory, maybe this was like the devil, or rain, you speak it and there it is. I watched him, studied him the way the rabbit studies the hound, alert to every twitch. He shifted his weight backward, away from me and averted his eyes. I thought, I am in trouble. His words were nondescript, something like, “We don’t yet know,” but the body language read, get it together, this is bad. The chaos in my head made me feel like I had taken off on a merry-go-round, fruitlessly searching for a still point and trying not to throw up. I was still grappling with his initial directive: call a surgeon. Like there wasn’t even time to go find one, I needed to be talking with one already. And already I was behind. I did call a surgeon. I remembered I knew one—my OB—I’ll call her Dr. A, someone I’d known since I was eighteen years old. But she had just retired from doing surgery. She set me up with one of her partners—Dr. B—for later that day. Dr. B looked me over quickly. I told her of the pain and that I was having trouble eating. She felt my pulse, looked at my tongue, checked my chart and said, “Hmm, I’m going to admit you to the hospital. Wait here.” I waited two hours to be admitted, like waiting for a hotel room to be cleaned and cleared. I sat in Dr. B’s waiting room, eyes closed, willing every part of my body to slow down. I was getting myself to the place I needed to be. Slow, steady breaths, one by one. I could make it; I would make it. When the bed was ready, I walked slowly over to the seventh floor. Before I went up though, I found the hallway with my dad’s picture in it. It was an old hallway connecting buildings off the beaten path. There—housing the photos of the Chiefs of Staff for the hospital—was my dad. He had died twenty-five years before from a brain tumor. But in this realm—his realm—he sat still and confident. Handsome and familiar. I made a silent plea, help me. I so wanted him looking over my shoulder. Then kept my steady pilgrimage to floor seven. The nurses seemed surprised to see me. I said, “Hi, I’m being admitted. I’m a patient. My doctor called earlier.” I felt a need to explain myself as they looked doubtful, pursed lips, sharp tilt of the head. I seemed to be doing this all wrong. But they checked “the board,” and there was my name. I had a place. Their faces eased; I got into a gown and slowly laid back into bed. I was dehydrated, hungry, and panting to get my breath, butterfly pulse. Once I had an IV and pain meds, Dr. B came in at the end of her day. “Wow, you look so much better. I thought you were crashing. We’ll get you an MRI, maybe do the surgery tonight. I should get the results around