NONE OF US SHOWED UP HERE WITHOUT CONTEXT

An interview with Sayantani Dasgupta on her new collection of essays, Brown Women Have Everything, by Keegan Lawler

Editor’s Note

By way of introduction to former BOR contributor Sayantani Dagupta’s writing—and, for that matter, to Keegan Lawler’s thoughtful, astute interview questions—I must first offer some context. Lawler, Dasgupta, and I all met at the University of Idaho in the quaint collegiate hamlet of Moscow, just shy of ten years ago. At the time, Dasgupta was a professor in the English department teaching creative writing; I was an MFA candidate in creative nonfiction; and Lawler was an undergraduate creative writer and English major. In 2017, I served as Dasgupta’s graduate TA in an intermediate creative nonfiction workshop in which Lawler was a standout student. The three of us established a relationship which, despite the passing of time and divergence of our geographical and career moves, endures in its compulsion to write personal and collective histories investigating the roots of identity and meaning across gender, race, class, place, and generations. I distinctly recall both Sayantani and Keegan in that workshop classroom—their writing, their ideas, their approaches to pedagogy and peer feedback, respectively—and have felt those memories resurface in my own teaching and learning ever since.

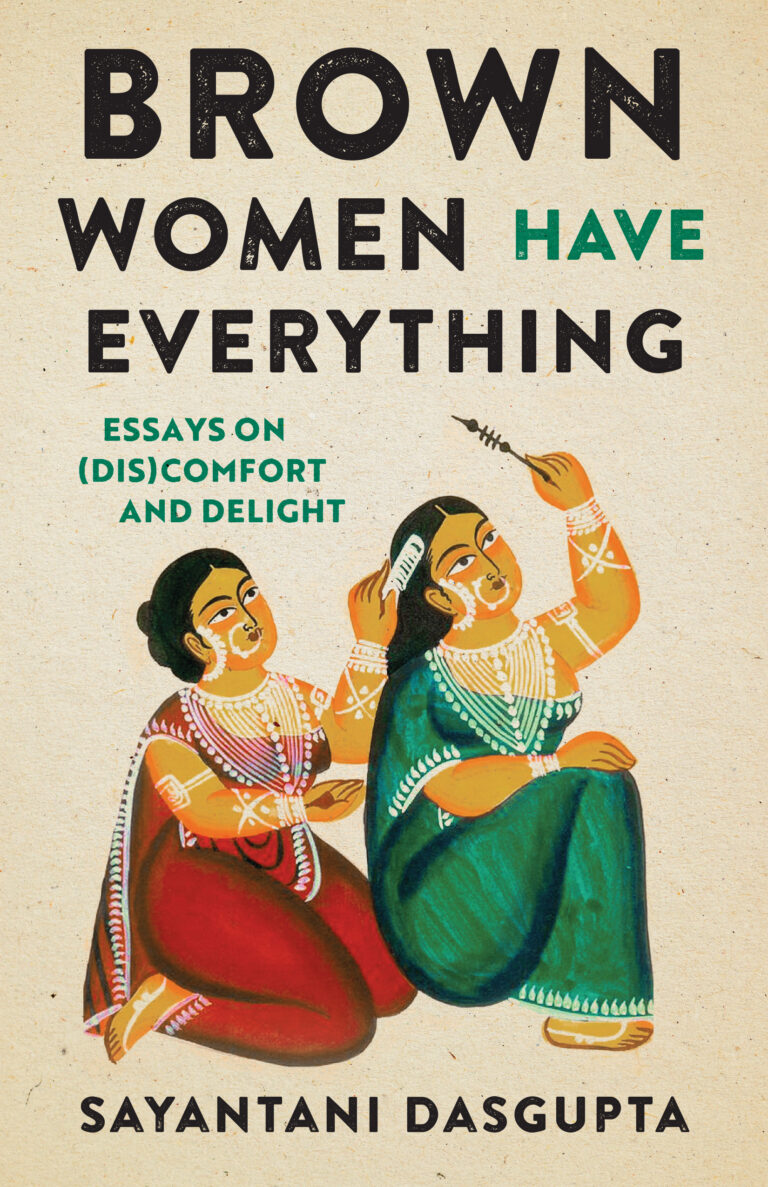

It is therefore fitting that Lawler’s conversation with Dasgupta about her latest collection, Brown Women Have Everything: Essays on (Dis)Comfort and Delight, hinges on the power of history and context, and lessons in writing and relatability passed down from Sayantani’s own family. I’m so happy to share the conversation with Blood Orange Review’s readers in celebration of Brown Women Have Everything’s publication (October 2024, The University of North Carolina Press), and to share insights into the writing of a collection, like our writerly friendships, that champions “the ties that bind our disparate, global lives together.”

-Lauren W. Westerfield, Editor-in-chief, Blood Orange Review

It is therefore fitting that Lawler’s conversation with Dasgupta about her latest collection, Brown Women Have Everything: Essays on (Dis)Comfort and Delight, hinges on the power of history and context, and lessons in writing and relatability passed down from Sayantani’s own family. I’m so happy to share the conversation with Blood Orange Review’s readers in celebration of Brown Women Have Everything’s publication (October 2024, The University of North Carolina Press), and to share insights into the writing of a collection, like our writerly friendships, that champions “the ties that bind our disparate, global lives together.”

-Lauren W. Westerfield, Editor-in-chief, Blood Orange Review

A Conversation with Sayantani Dasgupta and Keegan Lawleraf

KL: I had the pleasure of reading your new book while traveling, which was oddly perfect as I felt so much of it was about travel and who we find ourselves to be in new places. Each of these settings (Kolkata, New Delhi, Moscow, Wilmington, Viterbo, Bangladesh, Chicago, etc.) feels so vibrant. I was amazed at your ability to write complex portraits of places, most of which I’ve never been to. So, my first question is: how do you approach writing place in your work?

SD: It’s very important to me that the reader feels invited into my world. Too many times, while reading fiction and/or creative nonfiction, I have found myself struggling in terms of placing myself right into the scene where all the action is taking place. The writing itself may be lyrical and gorgeous, but as a reader, if I don’t have a strong sense of Place or Time, I am not one hundred percent on board with the author. This is why, and because Brown Women Have Everything does go to so many places, that getting Place right was crucial to the book. But then it raises the parallel question of what details to choose because places are vibrant with details. That decision of what details to pick, what to keep, and what to reject only becomes clear to me in subsequent drafts when I know what the essay is working toward, and I must choose wisely what will best serve it.

KL: Something you said to me once when we were at UI together was to write as if someone in Somalia was reading my work, which was very profound to me as an undergraduate, and has been advice I’ve returned to often since. At the time, being a young writer, I hadn’t even considered that anyone I didn’t know would be reading my work. To imagine my work being read by someone with so little context of the places I come from completely expanded whatever I thought of as my “audience” at the time.

Does audience factor in when you consider how you choose details to build out that sense of place in your work?

SD: Thank you for telling me that. I was taught to consider my audience like that by my mother back when I was writing my very first tiny essays in school, at age seven or eight. It was neat to think that though I was only responding to a school assignment, the reader could potentially be someone who was not my teacher and that I had to write in a way that would be interesting and meaningful to this person who didn’t know me or where I lived or what I liked to eat for lunch.

I try to keep that same mindset now. But not in the first draft. At least, I try not to. At that stage, I am, hopefully, only paying attention to what it is that I need to say. If I think of the audience, I will end up diluting whatever it is that I am trying to get to. In subsequent drafts and edits, I pay more attention to the audience. And I remain mindful that it’s not my job to please everyone, so, my audience is also not everyone. At the same time, those I am trying to draw in, should feel welcomed into my world.

KL: I think so much of that sense of welcoming readers into your world comes about through your voice and tone. You have this ability to balance humor, wonder, wit, and vulnerability in your work that gives such a full sense of your experiences. I think of essays like “Valentine’s Day: A Fourteen-Point Meditation on Love and Other Fiery Monsters,” “Forty Days in Italy,” and “Killer Dinner” as prime examples of this.

When you revised these drafts, how much of a consideration was the tone for you? Or is that something you found in your early drafts and just tried to refine around?

SD: What a great question! All these terms such as tone, voice, tension etc., that we in creative writing programs obsess over, no regular reader thinks about them, at least not consciously. I remember how confusing they were for me in my first couple of semesters as an MFA student. I had never had a creative writing class until that time and my undergrad and grad background before then had been in history.

What I know now, and I didn’t then, is that every writer’s tone and voice are both constantly evolving. And that’s because we, as human beings, as sentient creatures, are constantly evolving. So my tone in Fire Girl, my first book of essays, was true to who I was then. I think the tone now is freer, and a lot of that has to do with growing older and gaining more confidence in myself as a writer and teacher. Who knows what my tone will become five years from now!

KL: You mentioning your degrees in history makes me think of the first essay in the collection, “Becoming This Brown Woman, or, Three Glorious Accidents,” which reminds me of an oral family history. The kind of story that is told repeatedly over the years. In those stories, it can feel like things are predetermined. Of course, your maternal grandfather would choose the letter from your paternal grandfather over others. But re-reading now, I’m also realizing it’s an essay about a rapidly changing, post-colonial India. Do you think history plays a role in personal essays for you?

SD: I am glad you thought of oral stories when you read that essay! I don’t think I was consciously tapping into the way oral stories travel from one generation to another, but I suppose subconsciously it must have been on my mind. I come from a family of storytellers and when I was growing up, I heard stories from both sides of my grandparents about where we come from, our ancestral places, stories from Hindu mythology, etc. I think being fascinated and interested in history is just the next step. It’s still stories, just more formalized and structured. I am always puzzled when I meet people who don’t think their present-day circumstances and personalities are intricately braided and shaped by their forefathers and foremothers. Everyone came from someplace and certain, specific people. None of us showed up here without context. So yes, history and historical research play a very important role in my storytelling and in my examination of Self.

KL: I like that. None of us showed up here without context. Speaking of context, I’m curious, and perhaps this is more a question for those of us who love hearing behind the scenes details, how did you settle on sequencing for the book? The essays include examinations on American gun culture, racism, belonging, food and family, multilingualism, etc., but it all feels so interwoven. As someone who has followed your work for a while (and owns all the books— even the limited-edition chapbook!), I also know these essays were written over a span of a few years, so I’m curious how you went about sequencing all these pieces?

SD: First, thank you for reading and following my work! Having had you as a student, it has been an absolute delight to witness your writing journey over the years, and I am so excited for what’s to come. As regards this collection, I must give a shout-out to my excellent editor Cate Hodorowicz. The essays were somewhat differently arranged when I submitted the manuscript. Cate thought it best to play with structures and also suggested alternating the more serious ones with the others. We had a few conversations around this and ultimately settled on the order you see in the book now.

KL: On Kiese Laymon and Deesha Philyaw’s podcast, Reckon True Stories, they always ask their guests about their favorite sentence they’ve ever written. For my last question, I want to ask a slightly adapted version: what is your favorite sentence from the book?

SD: This is truly a hard question. For now, I am going to opt for a sentence that’s in the first essay, “Three Glorious Accidents.” This is the part where I am reflecting over my parents’ journey from Kolkata to New Delhi. “I learned that there is honor and dignity in pursuing your dreams, in moving out of places and worlds that are comfortable and familiar, in making mistakes, and perhaps even in being homesick.”

If you check back with me in a month, I am sure I will pick something else. For now, though, this sentence feels like it most represents me and this book, and it’s easily one of the most vital lessons I learned from my parents when I was a kid.

SD: It’s very important to me that the reader feels invited into my world. Too many times, while reading fiction and/or creative nonfiction, I have found myself struggling in terms of placing myself right into the scene where all the action is taking place. The writing itself may be lyrical and gorgeous, but as a reader, if I don’t have a strong sense of Place or Time, I am not one hundred percent on board with the author. This is why, and because Brown Women Have Everything does go to so many places, that getting Place right was crucial to the book. But then it raises the parallel question of what details to choose because places are vibrant with details. That decision of what details to pick, what to keep, and what to reject only becomes clear to me in subsequent drafts when I know what the essay is working toward, and I must choose wisely what will best serve it.

KL: Something you said to me once when we were at UI together was to write as if someone in Somalia was reading my work, which was very profound to me as an undergraduate, and has been advice I’ve returned to often since. At the time, being a young writer, I hadn’t even considered that anyone I didn’t know would be reading my work. To imagine my work being read by someone with so little context of the places I come from completely expanded whatever I thought of as my “audience” at the time.

Does audience factor in when you consider how you choose details to build out that sense of place in your work?

SD: Thank you for telling me that. I was taught to consider my audience like that by my mother back when I was writing my very first tiny essays in school, at age seven or eight. It was neat to think that though I was only responding to a school assignment, the reader could potentially be someone who was not my teacher and that I had to write in a way that would be interesting and meaningful to this person who didn’t know me or where I lived or what I liked to eat for lunch.

I try to keep that same mindset now. But not in the first draft. At least, I try not to. At that stage, I am, hopefully, only paying attention to what it is that I need to say. If I think of the audience, I will end up diluting whatever it is that I am trying to get to. In subsequent drafts and edits, I pay more attention to the audience. And I remain mindful that it’s not my job to please everyone, so, my audience is also not everyone. At the same time, those I am trying to draw in, should feel welcomed into my world.

KL: I think so much of that sense of welcoming readers into your world comes about through your voice and tone. You have this ability to balance humor, wonder, wit, and vulnerability in your work that gives such a full sense of your experiences. I think of essays like “Valentine’s Day: A Fourteen-Point Meditation on Love and Other Fiery Monsters,” “Forty Days in Italy,” and “Killer Dinner” as prime examples of this.

When you revised these drafts, how much of a consideration was the tone for you? Or is that something you found in your early drafts and just tried to refine around?

SD: What a great question! All these terms such as tone, voice, tension etc., that we in creative writing programs obsess over, no regular reader thinks about them, at least not consciously. I remember how confusing they were for me in my first couple of semesters as an MFA student. I had never had a creative writing class until that time and my undergrad and grad background before then had been in history.

What I know now, and I didn’t then, is that every writer’s tone and voice are both constantly evolving. And that’s because we, as human beings, as sentient creatures, are constantly evolving. So my tone in Fire Girl, my first book of essays, was true to who I was then. I think the tone now is freer, and a lot of that has to do with growing older and gaining more confidence in myself as a writer and teacher. Who knows what my tone will become five years from now!

KL: You mentioning your degrees in history makes me think of the first essay in the collection, “Becoming This Brown Woman, or, Three Glorious Accidents,” which reminds me of an oral family history. The kind of story that is told repeatedly over the years. In those stories, it can feel like things are predetermined. Of course, your maternal grandfather would choose the letter from your paternal grandfather over others. But re-reading now, I’m also realizing it’s an essay about a rapidly changing, post-colonial India. Do you think history plays a role in personal essays for you?

SD: I am glad you thought of oral stories when you read that essay! I don’t think I was consciously tapping into the way oral stories travel from one generation to another, but I suppose subconsciously it must have been on my mind. I come from a family of storytellers and when I was growing up, I heard stories from both sides of my grandparents about where we come from, our ancestral places, stories from Hindu mythology, etc. I think being fascinated and interested in history is just the next step. It’s still stories, just more formalized and structured. I am always puzzled when I meet people who don’t think their present-day circumstances and personalities are intricately braided and shaped by their forefathers and foremothers. Everyone came from someplace and certain, specific people. None of us showed up here without context. So yes, history and historical research play a very important role in my storytelling and in my examination of Self.

KL: I like that. None of us showed up here without context. Speaking of context, I’m curious, and perhaps this is more a question for those of us who love hearing behind the scenes details, how did you settle on sequencing for the book? The essays include examinations on American gun culture, racism, belonging, food and family, multilingualism, etc., but it all feels so interwoven. As someone who has followed your work for a while (and owns all the books— even the limited-edition chapbook!), I also know these essays were written over a span of a few years, so I’m curious how you went about sequencing all these pieces?

SD: First, thank you for reading and following my work! Having had you as a student, it has been an absolute delight to witness your writing journey over the years, and I am so excited for what’s to come. As regards this collection, I must give a shout-out to my excellent editor Cate Hodorowicz. The essays were somewhat differently arranged when I submitted the manuscript. Cate thought it best to play with structures and also suggested alternating the more serious ones with the others. We had a few conversations around this and ultimately settled on the order you see in the book now.

KL: On Kiese Laymon and Deesha Philyaw’s podcast, Reckon True Stories, they always ask their guests about their favorite sentence they’ve ever written. For my last question, I want to ask a slightly adapted version: what is your favorite sentence from the book?

SD: This is truly a hard question. For now, I am going to opt for a sentence that’s in the first essay, “Three Glorious Accidents.” This is the part where I am reflecting over my parents’ journey from Kolkata to New Delhi. “I learned that there is honor and dignity in pursuing your dreams, in moving out of places and worlds that are comfortable and familiar, in making mistakes, and perhaps even in being homesick.”

If you check back with me in a month, I am sure I will pick something else. For now, though, this sentence feels like it most represents me and this book, and it’s easily one of the most vital lessons I learned from my parents when I was a kid.